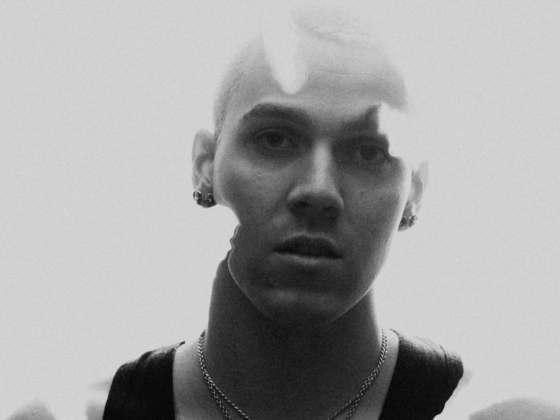

Party Nails shares dreamy and daring music video for "Trigger Warning" [Video]

Party Nails is the captivating musical project of singer, songwriter, producer, musician and engineer Elana Carroll. The LA based via New York creator has recently been making waves and turning…

Share