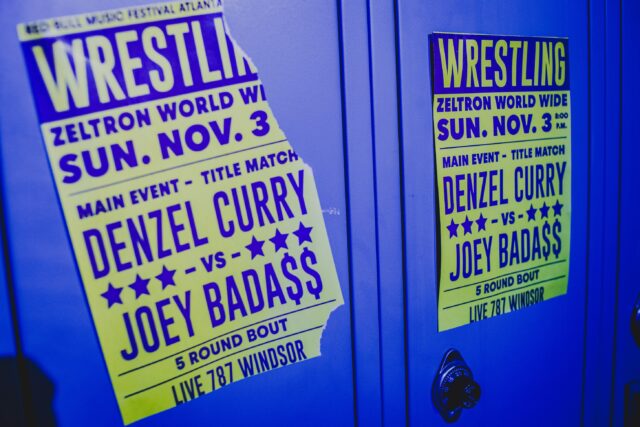

On November 3rd, Denzel Curry brought his special Zeltron Worldwide event to the city of Atlanta on the third day of the first annual Red Bull Music Festival Atlanta. The south-Florida rapper challenged his peer in the industry, Joey Bada$$ to a five-round bout of a showcase of performances of their best songs.

The unique concept is presented as a wrestling lineup where there is a spectacle of wrestling in the stage ring for the opening entertainment. The main battle on the card, however, is Denzel Curry up against a challenger. Red Bull and Curry worked together to put the Zeltron experience into fruition at first last year in Miami with the debut of Zeltron vs. Zombies, as the rapper and his crew faced off against the Flatbush Zombies, a New York trio.

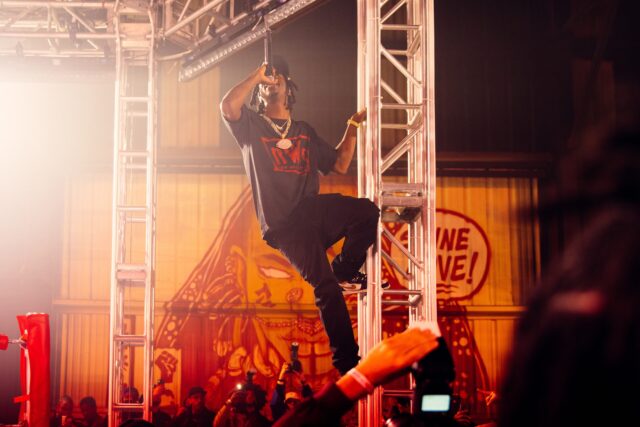

This time, Curry competed against a lyricist that he once opened for on the 2015 World Domination Tour, Joey Bada$$. The event was hosted by comedian, Desi Banks. Hundreds of fans showed up as they performed some of their fan favorites. Other artists came in support of the event in Atlanta like Pastor Troy, the ATL-legend who performed “No Mo Play In G.A.”, and Reese LaFlare came out to contribute by performing "Costa Rica".

On stage, Joey even proposed a challenge to Harlem's, A$AP Mob. We'll see if Red Bull and Curry can get that setup, but for now there's no word of a future date.

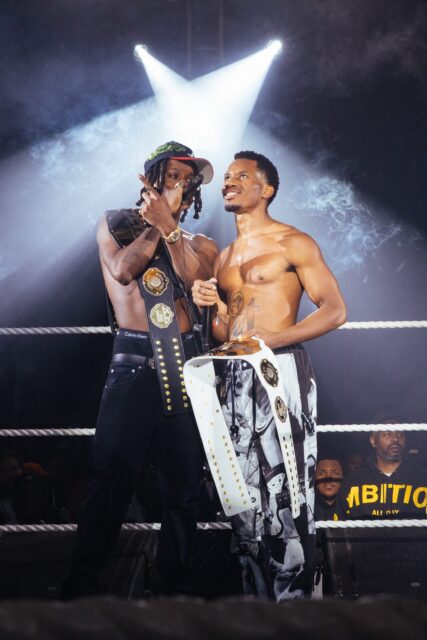

After Denzel Curry ended the last round performing his smash hit, "Ultimate", Joey and a handful of friends and artists joined the ring to let loose for one last song. The friendly competition ended with both emcees receiving a championship belt and the two used the opportunity to extend public praises to each other. The Red Bull Zeltron Worldwide show is a display like no other.

The day following the Atlanta show, Curry tweets:

ZELTRON WORLD WIDE 2020

MIAMI

NEW YORK CITY

OAKLAND@ the battles you want to see…

GO!!!

— Denzel Curry (@denzelcurry) November 4, 2019