Grammy-nominated rapper Lil Yachty, known for his beaded red locks and autotuned "bubblegum trap," has partnered with digital art marketplace Nifty Gateway to sell his own piece of digital art. Yachty's artwork is titled "YachtyCoin," and is currently being auctioned off until today at 7 p.m. Eastern Time.

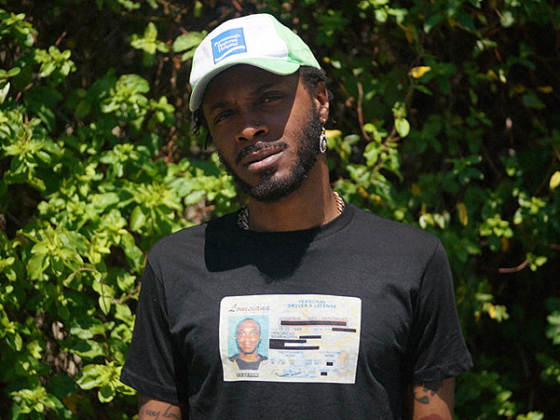

Lil Yachty previewed his YachtyCoin piece on Instagram late last week.

View this post on Instagram

Lil Yachty's foray into the crypto world kicked off on December 10th, when his social token $YACHTY garnered upwards of $375,000 in total sales. Digital currency like $YACHTY circumvents the physical limitations of a post-COVID world and offers innovative ways to connect with fans, rewarding diehards with exclusive perks like signed memorabilia and access to virtual parties.

The rapper's collaboration with Nifty Gateway's blockchain-powered platform is a savvy move following the release of $YACHTY. Nifty Gateway, owned by bitcoin billionaires Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, i.e., The Social Network twins, has previously worked with big-name musicians like 3LAU and world-renowned artists Michael Kagan and Kenny Schachter to launch digital-only art collections.

As the music industry, and most other forms of entertainment, become increasingly remote, artists will continue to seek unconventional ways to monetize their art and engage fans digitally. Given the current state of live events, Lil Yachty's cryptocurrency experiment may provide fans the closest thing to backstage passes.