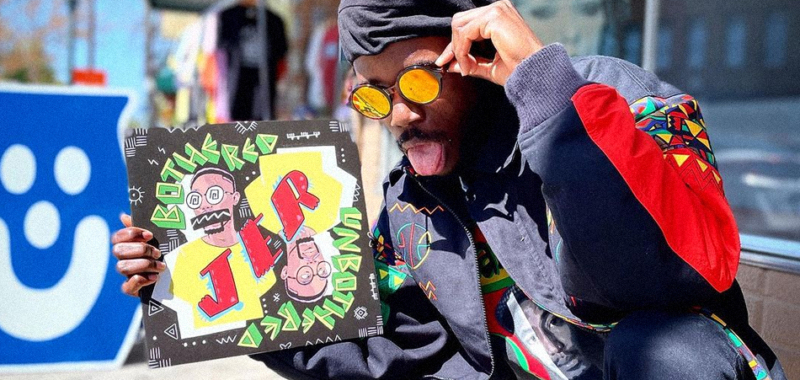

JER discusses creating community through ska and creating their debut LP 'BOTHERED/ UNBOTHERED' (INTERVIEW)

I sat down with one of the most prodigious names in the current U.S ska scene, JER, aka Skatune Network to discuss the popularity of ska in Mexico, the radical…

Share